Joseph Mitchell, "The Old House at Home"

Joseph Mitchell’s classic piece of literary journalism, published in 1940, paints a vivid portrait of a neighborhood saloon in New York’s Lower East Side.

Annotated version

Notes by Austin Woerner

Excerpts

1.

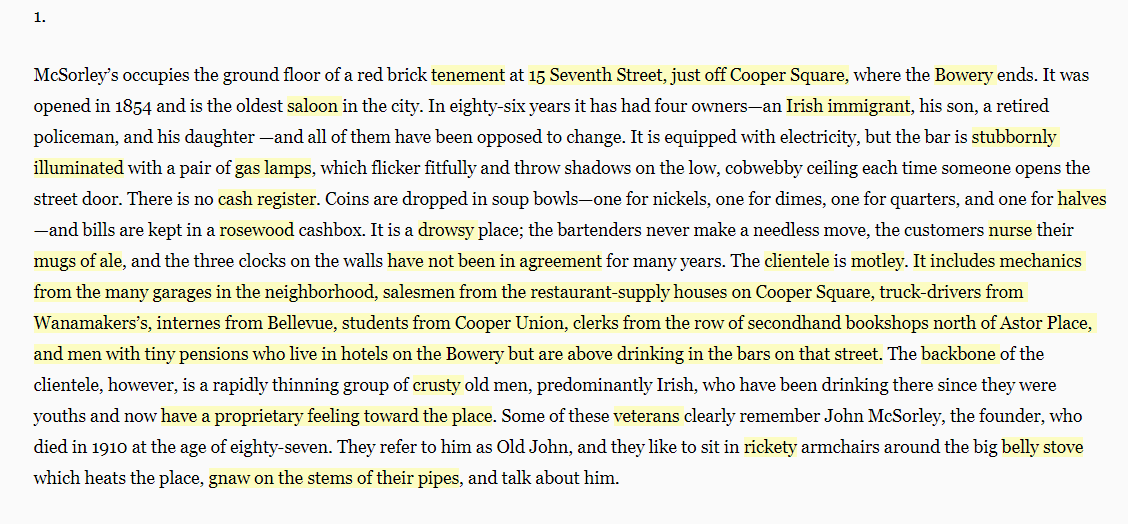

McSorley’s occupies the ground floor of a red brick tenement at 15 Seventh Street, just off Cooper Square, where the Bowery ends. It was opened in 1854 and is the oldest saloon in the city. In eighty-six years it has had four owners—an Irish immigrant, his son, a retired policeman, and his daughter —and all of them have been opposed to change. It is equipped with electricity, but the bar is stubbornly illuminated with a pair of gas lamps, which flicker fitfully and throw shadows on the low, cobwebby ceiling each time someone opens the street door. There is no cash register. Coins are dropped in soup bowls—one for nickels, one for dimes, one for quarters, and one for halves—and bills are kept in a rosewood cashbox. It is a drowsy place; the bartenders never make a needless move, the customers nurse their mugs of ale, and the three clocks on the walls have not been in agreement for many years. The clientele is motley. It includes mechanics from the many garages in the neighborhood, salesmen from the restaurant-supply houses on Cooper Square, truck-drivers from Wanamakers’s, internes from Bellevue, students from Cooper Union, clerks from the row of secondhand bookshops north of Astor Place, and men with tiny pensions who live in hotels on the Bowery but are above drinking in the bars on that street. The backbone of the clientele, however, is a rapidly thinning group of crusty old men, predominantly Irish, who have been drinking there since they were youths and now have a proprietary feeling toward the place. Some of these veterans clearly remember John McSorley, the founder, who died in 1910 at the age of eighty-seven. They refer to him as Old John, and they like to sit in rickety armchairs around the big belly stove which heats the place, gnaw on the stems of their pipes, and talk about him.

2.

In his time, Old John catered to the Irish and German workingmen—carpenters, tanners, bricklayers, slaughter-house butchers, teamsters, and brewers—who populated the Seventh Street neighborhood, selling ale in pewter mugs at five cents a mug and putting out a free lunch inflexibly consisting of soda crackers, raw onions, and cheese; present-day customers are wont to complain that some of the cheese Old John laid out on opening night in 1854 is still there. Adjacent to the free lunch he kept a quart crock of tobacco and a rack of clay and corncob pipes—the purchase of an ale entitled a man to a smoke on the house; the rack still holds a few of the communal pipes. Old John was thrifty and was able to buy the tenement—it is five stories high and holds eight families —about ten years after he opened the saloon in it. He distrusted banks and always kept his money in a cast-iron safe; it still stands in the back room, but its doors are loose on their hinges and there is nothing in it but an accumulation of expired saloon licences and several McSorley heirlooms, including Old John’s straight razor. He lived with his family in a flat directly over the saloon and got up every morning at five; he walked to the Battery and back before breakfast, no matter what the weather. He unlocked the saloon at seven, swept it out himself, and spread sawdust on the floor. Until he became too feeble to manage a racing sulky, he always kept a horse and a nanny goat in a stable around the corner on St. Mark’s Place. He kept both animals in the same stall, believing, like many horse-lovers, that horses should have company at night. During the lull in the afternoon a stable-hand would lead the horse around to a hitching block in front of the saloon, and Old John, wearing his bar apron, would stand on the curb and groom the animal. A customer who wanted service would tap on the window and Old John would drop his currycomb, step inside, draw an ale, and return at once to the horse. On Sundays he entered sulky races on uptown highways.

3.

Old John was quirky. He was normally affable but was subject to spells of unaccountable surliness during which he would refuse to answer when spoken to. He went bald in early manhood and began wearing scraggly, patriarchal sideburns before he was forty. Many photographs of him are in existence, and it is obvious that he had a lot of unassumed dignity. He patterned his saloon after a public house he had known in Ireland and originally called it the Old House at Home; around 1908 the signboard blew down, and when he ordered a new one he changed the name to McSorley’s Old Ale House. That is still the official name; customers never have called it anything but McSorley’s. Old John believed it impossible for men to drink with tranquillity in the presence of women; there is a fine back room in the saloon, but for many years a sign was nailed on the street door, saying, “Notice. No Back Room in Here for Ladies.” In McSorley’s entire history, in fact, the only woman customer ever willingly admitted was an addled old peddler called Mother Fresh-Roasted, who claimed her husband died from the bite of a lizard in Cuba during the Spanish-American War and who went from saloon to saloon on the lower East Side for a couple of generations hawking peanuts, which she carried in her apron. On warm days, Old John would sell her an ale, and her esteem for him was such that she embroidered him a little American flag and gave it to him one Fourth of July; he had it framed and placed it on the wall above his brassbound ale pump, and it is still there. When other women came in, Old John would hurry forward, make a bow, and say, “Madam, I’m sorry, but we don’t serve ladies.” This technique is still used.

[…]

4.

Old John had a remarkable passion for memorabilia. For years he saved the wishbones of Thanksgiving and Christmas turkeys and strung them on a rod connecting the pair of gas lamps over the bar; the dusty bones are invariably the first thing a new customer gets inquisitive about. Not long ago, a Johnny-come-lately infuriated one of the bartenders by remarking, “Maybe the old boy believed in voodoo.” Old John decorated the partition between barroom and back room with banquet menus, autographs, starfish shells, theatre programs, political posters, and worn-down shoes taken off the hoofs of various race and brewery horses. Above the entrance to the back room he hung; a shillelagh and a sign: “BE GOOD OR BEGONE.” On one wall of the barroom he placed portraits of horses, steamboats, Tammany bosses, jockeys, actors, singers, and assassinated statesmen; there are many excellent portraits of Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley. On the same wall he hung framed front pages of old newspapers; one, from the London Times for June 22, 1815, contains a paragraph on the beginning of the battle of Waterloo, in the lower right-hand corner, and another, from the New York Herald of April 15, 1865, has a single-column story on the shooting of Lincoln. He blanketed another wall with lithographs and steel engravings. One depicts Garfield’s deathbed. Another is entitled “The Great Fight.” It was between Tom Hyer and Yankee Sullivan, both bare-knuckled, at Still Pond Heights, Maryland, in 1849. It was won by Hyer in sixteen rounds, and the prize was $10,000. The judges wore top hats. The brass title tag on another engraving reads, “Rescue of Colonel Thomas J. Kelly and Captain Timothy Deacy by Members of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood from the English Government at Manchester, England, September 18, 1867.” A copy of the Emancipation Proclamation is on this wall; so, almost inevitably, is a facsimile of Lincoln’s saloon licence. An engraving of Washington and his generals hangs next to an engraving of a session of the Great Parliament of Ireland. Eventually Old John covered practically every square inch of wall space between wainscot and ceiling with pictures and souvenirs. They are still in good condition, although spiders have strung webs across many of them. New customers get up on chairs and spend hours studying them.

[…]

(In the part omitted here, Mitchell describes the history of the saloon and its four different owners down the years. Note: Kelly “the Floorwalker,” mentioned in the following paragraphs, is a customer who spends most of his days in McSorley’s and serves as a kind of volunteer waiter, even though he’s not employed by the saloon.)

5.

To a steady McSorley customer, most other New York saloons seem feminine and fit only for college boys and women; the atmosphere in them is so tense and disquieting that he has to drink himself into a coma in order to stand it. In McSorley’s, the customers are self-sufficient; they never try to impress each other. Also, they are not competitive. In other saloons if a man tells a story, good or bad, the man next to him laughs perfunctorily and immediately tries to tell a better one. It is possible to relax in McSorley’s. For one thing, it is dark and gloomy, and repose comes easy in a gloomy place. Also, there is a thick, musty smell that acts as a balm to jerky nerves; it is really a rich compound of the smells of pine sawdust, tap drippings, pipe tobacco, coal smoke, and onions. A Bellevue interne once said that for many mental disturbances the smell in McSorley’s is more beneficial than psychoanalysis. It is an utterly democratic place. A mechanic in greasy overalls gets as much attention as an executive from Wanamaker’s. The only customer the bartenders brag about is Police Inspector Matthew J. McGrath, who was a shot-and hammer-thrower in four Olympics and is called Mighty Matt.

[…]

6.

McSorley’s bar is short, accommodating approximately ten elbows, and is shored up with iron pipes. It is to the right as you enter. To the left is a row of armchairs with their stiff backs against the wainscoting. The chairs are rickety; when a fat man is sitting in one, it squeaks like new shoes every time he takes a breath. The customers believe in sitting down; if there are vacant chairs, no one ever stands at the bar. Down the middle of the room is a row of battered tables. Their tops are always sticky with spilled ale. In the centre of the room stands the belly stove, which has an isinglass door and is exactly like the stoves in Elevated stations. All winter Kelly keeps it red hot. “Warmer you get, drunker you get,” he says. Some customers prefer mulled ale. They keep their mugs on the hob until the ale gets hot as coffee. A sluggish cat named Minnie sleeps in a scuttle beside the stove. The floor boards are warped, and here and there a hole has been patched with a flattened-out soup can. The back room looks out on a blind tenement court. In this room are three big, round dining-room tables. The kitchen is in one corner of the room; Mike keeps a folding boudoir screen around the gas range, and pots, pans, and paper bags of groceries are stored on the mantelpiece. While he peels potatoes, he sits with early customers at a table out front, holding a dishpan in his lap and talking as he peels. The fare in McSorley’s is plain, cheap, and well cooked. Mike’s specialties are goulash, frankfurters and sauerkraut, and hamburgers blanketed with fried onions. He scribbles his menu in chalk on a slate which hangs in the barroom and consistently misspells four dishes out of five. There is no waiter. During the lunch hour, if Mike is too busy to wait on the customers, they grab plates and help themselves out of the pots on the range. They eat with their hats on and they use toothpicks. Mike refers to food as “she.” For example, if a customer complains that the goulash is not as good as it was last Wednesday, he says, “No matter how not as good she is, she’s good enough for you.”

7.

The saloon opens at eight. Mike gives the floor a lick and a promise and throws on clean sawdust. He replenishes the free-lunch platters with cheese and onions and fills a bowl with cold, hard-boiled eggs, five cents each. Kelly shows up. The ale truck makes its delivery. Then, in the middle of the morning, the old men begin shuffling in. Kelly calls them “the steadies.” The majority are retired laborers and small businessmen. They prefer McSorley’s to their homes. A few live in the neighborhood, but many come from a distance. One, a retired operator of a chain of Bowery flophouses, comes in from Sheepshead Bay practically every day. On the day of his retirement, this man said, “If my savings hold out, I’ll never draw another sober breath.” He says he drinks in order to forget the misery he saw in his flophouses; he undoubtedly saw a lot of it, because he often drinks twenty-five mugs a day, and McSorley’s ale is by no means weak. Kelly brings the old men their drinks. To save him a trip, they usually order two mugs at a time. Most of them are quiet and dignified; a few are eccentrics. About twelve years ago one had to leap out of the path of a speeding automobile on Third Avenue; he is still furious. He mutters to himself constantly. Once, asked what he was muttering about, he said, “Going to buy a shotgun and stand on Third Avenue and shoot at automobiles.” “Are you going to aim at the tires?” he was asked. “Why, hell no!” he said. “At the drivers. Figure I could kill four or five before they arrested me. Might kill more if I could reload fast enough.”

8.

Only a few of the old men have enough interest in the present to read newspapers. These patrons sit up front, to get the light that comes through the grimy street windows. When they grow tired of reading, they stare for hours into the street. There is always something worth looking at on Seventh Street. It is one of those East Side streets completely under the domination of kids. While playing stickball, they keep great packing-box fires going in the gutter; sometimes they roast mickies in the gutter fires. Drunks reel over from the Bowery and go to sleep in doorways, and the kids give them hotfoots with kitchen matches. In McSorley’s the free-lunch platters are kept at the end of the bar nearer the street door, and several times every afternoon kids sidle in, snatch handfuls of cheese and slices of onion, and dash out, slamming the door. This never fails to amuse the old men.

9.

The stove overheats the place and some of the old men are able to sleep in their chairs for long periods. Occasionally one will snore, and Kelly will rouse him, saying, “You making enough racket to wake the dead.” Once Kelly got interested in a sleeper and clocked him. Two hours and forty minutes after the man dozed off, Kelly became uneasy—“Maybe he died,” he said—and shook him awake. “How long did I sleep?” the man asked. “Since the parade,” Kelly said. The man rubbed his eyes and asked, “Which parade?” “The Paddy’s Day parade, two years ago,” Kelly said scornfully. “Jeez!” the man said. Then he yawned and went back to sleep. Kelly makes jokes about the regularity of the old men. “Hey, Eddie,” he said one morning, “old man Ryan must be dead!” “Why?” Mullins asked. “Well,” Kelly said, “he ain’t been in all week.” In summer they sit in the back room, which is as cool as a cellar. In winter they grab the chairs nearest the stove and sit in them, as motionless as barnacles, until around six, when they yawn, stretch, and start for home, insulated with ale against the dreadful loneliness of the old. “God be wit’ yez,” Kelly says as they go out the door. ♦